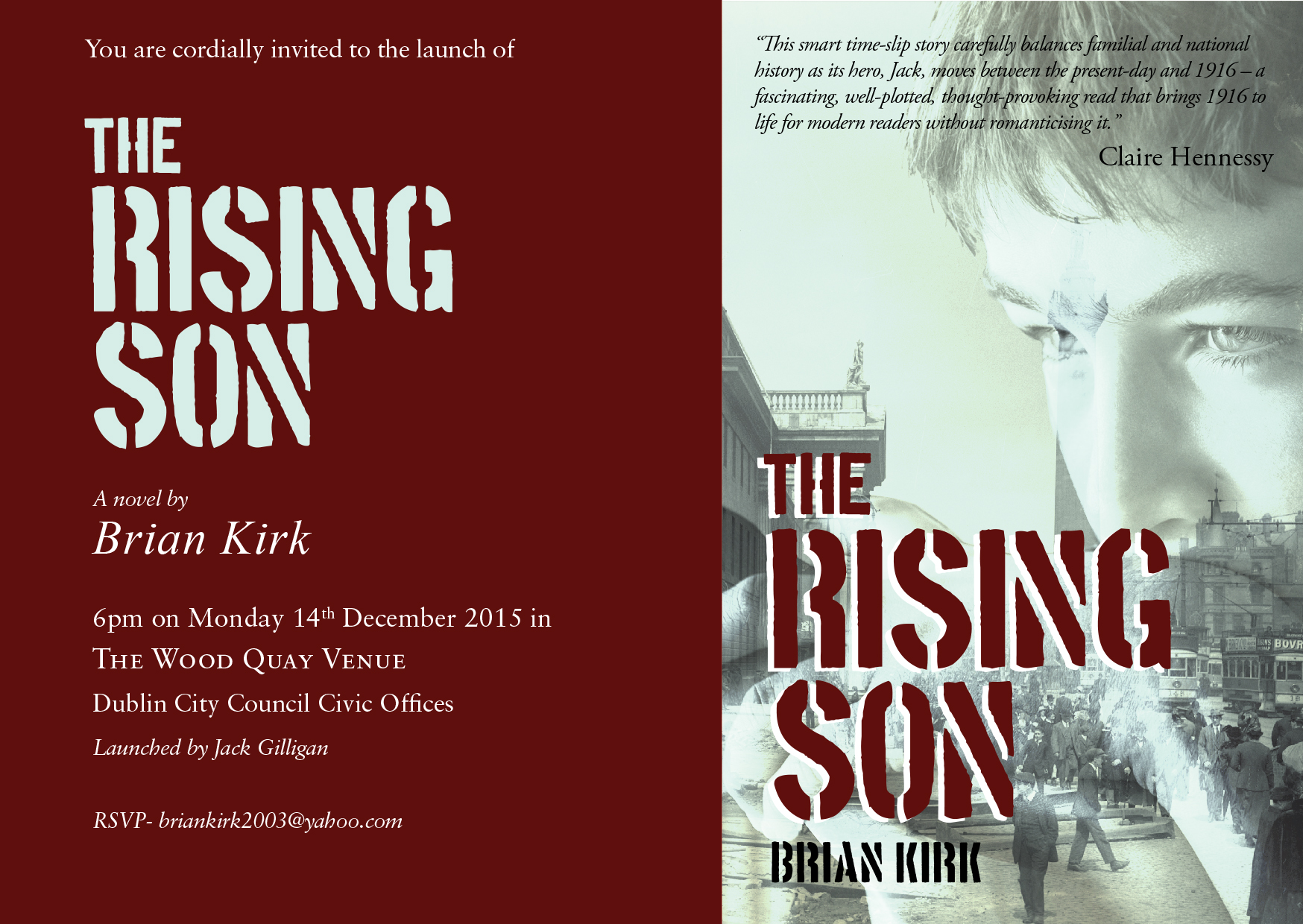

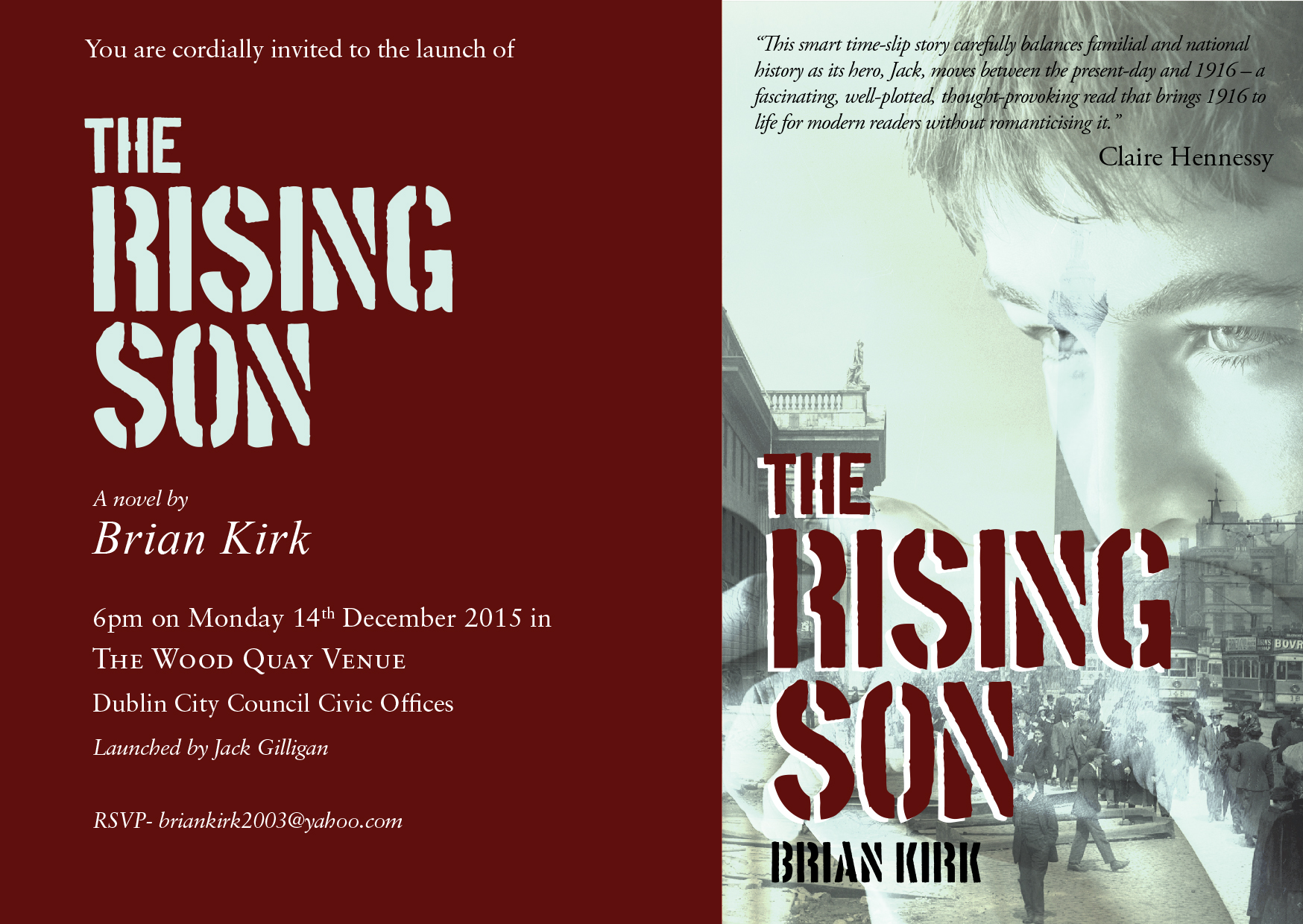

Okay, so the cover is taking a bit longer than we expected. It’s about bridging a gap between then, as shown above, and now in a way that might appeal to a modern reader. Despite years of being told otherwise, apparently everybody judges books by their covers.

So in the meantime I thought I’d introduce you to some of the main characters in The Rising Son. Here follows the opening chapter. I hope you enjoy it and that it whets your appetite for what is still to come.

Chapter 1

On the second night in his grandfather’s house it all began. He was alone on a dark street, lit by occasional dim streetlights. There was a peculiar smell in the grey air, one that he could not name. In fact there was a mixture of smells; bad smells like the stench of farmyards for one, but many more besides. He was surprised to find that he was not afraid to be alone on this alien street. Part of him hoped that this was just a dream, but it felt more real than any dream he’d ever had before.

The street was empty, but in the distance he could hear a noise he thought might be thunder, or heavy barrels being rolled across cobblestones. He had the sense that the day had been hot, but now he felt the cool night air against his face and for a moment he thought of home. But it was just a word. He recognised the word, but he couldn’t attach a place or memory to it in his mind. In fact he couldn’t say where he was from, and in the same breath he realised he did not have a name. But once again the terror he should have felt at that moment was absent. In fact, he was barely there himself.

At the far end of the street he saw a figure approaching. It was a boy, roughly his own age. Jack was puzzled by the boy’s bare feet and strange clothing; knee-length trousers, an old dark jacket that was too big for him, a cap and scarf. The year before his mother had taken him to see a production of Oliver in the West End, and as he watched the boy, he thought of boys his own age acting the roles of Victorian child-villains.

‘Howya! Are ye lost?’

He was so surprised when the boy spoke, he did not answer for a few moments. It was as if he was watching a play, not from the stalls as you normally would, but from the stage itself. But now the boy had burst the magic bubble; he had spoken to a member of the audience and the illusion was shattered.

‘I’m… I suppose I am.’

The boy frowned.

‘Are you English?’

‘Yes, I mean, no – I suppose I’m Irish and English.’

‘You can’t be both these days – it’s one or the other. Come along with me and I’ll bring you where you’re going. Where do you live?’

‘I live with my grandfather, Michael O’Connor. It’s number 52 Haroldville Avenue.’

‘Shur that’s only round the corner, I’ll bring you there now. I’m Willie by the way.’

‘Jack.’

His name came to him as if from a great distance and it comforted him that he had a name again, and that he had a new friend too. They shook hands formally like old men.

‘Come on,’ Willie said.

They set off walking, their footsteps echoing on the empty street.

‘You must a left home in an awful hurry.’

‘What do you mean?’ Jack asked.

‘Them clothes a yours. You must be frozen.’

Jack looked down and saw that he was wearing only a t-shirt and light pyjama trousers with slippers on his feet.

‘Them shoes a yours look awful cosy but.’

‘They are,’ Jack said because he could think of nothing else to say to this strange boy.

They rounded the corner and Jack realised that they were now on his grandfather’s street, but it looked different somehow. Perhaps it was just the darkness; the streetlights gave off so little light and there were no lights on in any of the neighbours’ windows.

Suddenly there was a scattering of shouts at one end of the street and then a deafening high-pitched sound that seemed to echo off the fronts of the terraced houses – a kind of shrill singing or zinging. The air was filled with a new smell now. It was smoke. Jack recognised it straight away because he’d walked past the remnants of a burnt out house with his stepfather on their way to see Arsenal play one Saturday. Both boys threw themselves on the ground instinctively and whatever light there was had now been extinguished. Jack reached out a hand to feel for Willie but felt only the damp cold stone of the road. He shut his eyes tight and opened them again, but there was only darkness. He heard heavy boots running, coming closer, a momentary pause and then more gunfire. He screamed.

He woke in a sweat. The bedclothes were on the floor and he was wrapped only in an old tartan blanket he’d found on top of the wardrobe the night before when he was cold and couldn’t get to sleep. The room smelled of must and damp. There was another smell mixed in there too, he thought it could be smoke. He tried to open the window to let in some air but it was useless; it was painted shut – had been for years. Everything about this house was old and stuffy and reeked of the past.

The day before Jack’s grandfather had taken him into town for a treat. Since his mother had abandoned him he had been quiet and surly. On the way home they rode the tram along the quays until they came to the museum where they walked around the exhibits, and all the while his grandfather provided a constant commentary.

‘You must always remember Jack, that you are an Irish man. You may have been born in London and lived all your twelve years there, but you are as Irish as I am.’

Everything in the museum was old. That’s the way it was with museums – he knew this from trips with his mother to the British Museum and Natural History Museum. But it wasn’t just the museum; the whole city of Dublin seemed old to Jack – compared to London it was tired and small and enclosed, and the grey sky seemed to press down on the rooftops, trapping him, stopping him from being where he wanted to be, in London with his mother and his friends.

His Grandfather showed him the uniforms worn by British and Irish soldiers over the years, sometimes taking the time to read aloud from the information provided on panels beside the exhibits.

‘This is where we all come from Jack. It’s our history. Do you see?’ Grandad looked at the boy.

He was wasting his breath, Jack thought. There was no point to this. It was all in the past. That’s what history was – even he knew that. The past was no good to him. At best it was a distraction from the present. It was the future that worried Jack.

When he thought about the future he could feel his heartbeat race inside his chest and his head would grow light. His mother told him it was just a holiday, that she would be back to get him in a couple of weeks. She had some things to see to, that was all. He was a child, but he was not a fool. She was trying to patch things up with Matt, he knew that. His stepfather had left them a month before. For weeks before that Jack had stood on the landing at night and listened to them arguing. He didn’t know what the cause of their arguments was but he assumed, as children do, that it was his fault. Perhaps Matt didn’t want him; he wanted a boy of his own – he had said that before – but that was never going to happen, Mum said.

Matt wasn’t bad. He had always been good to Jack, and Jack had no expectation of him beyond the things he did for him. He took him to football or cricket practise, he made fried breakfasts on Saturdays and brought him to the Emirates Stadium to see Arsenal play; he called him mate and bought him ice-creams and football magazines. Jack was happy enough with that. But Matt wanted more – that was why he had said on one of those nights when they argued just before he moved out:

‘I want a child of my own, Kate – what’s so wrong with that?’

Jack took deep breaths and put his hand against his heart to feel the pulse quicken as he listened from the landing above.

Was Matt more important to his mother than he was? That was the question he was trying not to ask himself since he came here. When she said goodbye to him she hurried out the door. Her taxi was waiting, and she had a plane to catch. And when she was gone he looked at this old man, this stranger – his grandfather supposedly – and sensed that the old man was looking back at him and thinking the exact same thing.

His mother spoiled him. She indulged him. He came first, he always had done and Jack had grown accustomed to that. Something had changed somehow, but she was not about to tell him what that was or maybe she felt he was too young to understand. But he was not too young. In the absence of hard facts he feared the worst. Perhaps she didn’t want him anymore.

Now as they stood before an original copy of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, Jack tried to listen to his grandfather’s commentary, but it was useless. He was thinking about his mother, and about Matt, and what they might be saying at that very moment to each other about him.

‘Is Matt Irish, Grandad?’

‘No, Jack, he’s English.’

‘Is that why he and Mum can’t be together?’

Grandad laughed briefly, but stopped when he noticed Jack’s frowning face.

‘No. No. That has nothing to do with anything. Sometimes people disagree over things. It’s complicated, that’s all. You’ll understand when you’re older.’

The old man placed his hand gently on Jack’s head and ruffled his unruly dark hair. Why did everyone treat him like a baby?